pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

UnMuseum

Search

|

|

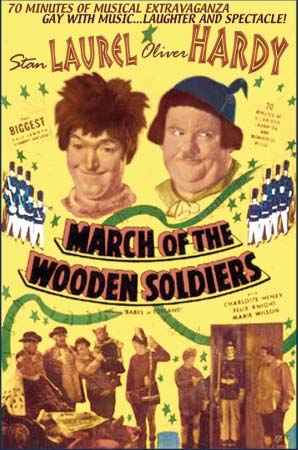

The Making of A Christmas Classic

As anyone who has grown up in North America knows, one of the traditions of the Christmas season is watching a holiday film on TV. Every year in the month or so between Thanksgiving and Christmas, television stations reach into their vaults and pull out some well-worn classics. Some have an obvious relationship with the holiday, like White Christmas or Miracle on 34th Street. Others, like, It's a Wonderful Life, have a more tenuous connection only really being associated with Christmas because of the many times they have been broadcast during that season. There is one film, however, that stands out from the rest because of a longevity that most Christmas films can only hope for. It is one of the oldest of these time-honored classics and, in many fans' opinions, the best. It was produced turning a turning point in the film industry and stars two icons of American comedy. Though originally released under the title Babes in Toyland, it is probably known best as March of the Wooden Soldiers. "Hal" Roach The story of this film starts with the famous American motion picture producer and director, Harold Eugene Roach, Sr.. After an adventurous youth, "Hal" Roach came to Hollywood in 1912 to work as an extra in the nascent film industry. An inheritance allowed him to start making his own films in 1915 and with his friend, famed comedian Harold Lloyd, Roach specialized in producing "two reel" humorous shorts. A standard reel of film back then was 1,000 feet and two of them together gave about 25 minutes of screen time. In theaters, one or two of these short subjects would be used before a feature length film.

Roach's business grew and he worked with a number of early, famous comedy stars including Lloyd, Will Rodgers, Charlie Chase and others. He also created a series of comedy films involving a group of children. The series, Our Gang, spawned 220 shorts and one feature-length film. The most famous comics who worked with Roach, however, were a short, thin man paired with a tall, heavyset man. Just their silhouettes were enough to identify them to any of their fans. They were to become perhaps the most well-known funny men of the early screen: Oliver Hardy and Stan Laurel. Laurel and Hardy Stan Laurel was born Arthur Stanley Jefferson in 1890 in Lancashire, England. His father was a well-known actor, director and playwright. As a young man, Arthur began his career on the stage at age 16 and worked his way up to be a featured comedian. In 1912 he emigrated to America and changed his name fearing that Stanley Jefferson was too long to fit on theatrical posters. He made his first film, Nuts, in May of 1917 and afterward appeared in a number of shorts for different producers. Oliver Hardy was born Norvell Hardy in 1892 in Georgia. After his father's death, he added his father's first name to his own becoming Oliver Norvell Hardy, though he was often referred to by his friends as just "Ollie" or "Babe." Hardy showed an early interest in film and by his late teens operated his own movie house in Milledgeville, Georgia. He soon got involved in the production end of the business working at Lubin Motion Pictures in Jacksonville, Florida. Though he started in the lighting department, he found his way on screen after about a year, acting in the 1914 production of Outwitting Dad. Over the next decade he made hundreds of short films working as a hero, villain or second banana. In 1917 he moved to California to join the growing film industry there, eventually working for Hal Roach in his stock company of players.

Laurel and Hardy's first film together was the 1919 production of The Lucky Dog from Sun-Lite Pictures. They did not assume their familiar on-screen identities together, however, until 1927 in a Roach film called The Second Hundred Years. The pairing was so successful that it was made permanent. Together their characters - two not too bright but eternally optimistic, innocent and child-like men in an adult world, charmed and amused audiences. They were soon Roach's most successful stars. While many actors never made a successful transition from silent pictures to sound when it appeared in the late 20's, the addition of dialog to their act seemed to make the team even more funny than before. By the early 1930's the film business began to change. Not only was there now sound along wih the picture, theaters were putting two feature length movies together in a "double-bill" and the demand for shorts was disappearing. Roach knew that he had to start producing full-length films and started looking around for material that could be made into movie scripts. From Operetta to Film Three decades before in 1903 an operetta (a light form of opera) entitled Babes in Toyland had opened in Chicago and toured a number of US cities before settling on Broadway for 192 performances. The show was composed by Victor Herbert in response to the tremendous success of the stage version of L. Frank Baum's book The Wizard of Oz. It used various characters from Mother Goose nursery rhymes to create a musical extravaganza. The original show was so successful that there were numerous national tours and revivals. It also inspired a rash of other "fairy-tale" themed productions over the next ten years.

The story of the operetta differs significantly from the later Roach film, though a few elements were retained. In it two orphans, Alan and Jane, are menaced by their wicked Uncle Barnaby, who wants to steal their inheritance. He attempts to kill them by shipwrecking them and later leaving them in the Forest of No Return. Barnaby also forces Alan's love, Mary Contrary, to marry him before he suffers a well deserved death and the lovers are reunited. Roach decided that the Herbert property was just what he needed to create a full-length musical movie production with his two most famous stars. He took the train to New York and successfully purchased the rights. The original stage production, however, was long on music but short on story. On the train back to California, Roach rewrote it to fit the needs of a film. Once back in California, Roach showed the script to Stan Laurel who didn't like it. Laurel, unlike his onscreen persona, was a perfectionist when it came to the duo's work. Concluding he could do better, he sat down with some of the studio's writing staff and hammered out a new version which, in turn, Roach didn't like. Laurel apparently won this particular disagreement, however, as it is his version which was finally put to film. The plot of the movie involves Laurel and Hardy taking on the storybook characters of "Ollie Dee" and "Stanley Dum." The two are boarders in the home of the Widow Peep whose family lives in an oversized shoe to which the wicked Silas Barnaby holds the mortgage. Mrs. Peep's oldest daughter, Little Bo-Peep, is in love with Tom-Tom, the piper's son, but her youthful beauty has attracted the unholy attentions of the elderly Barnaby, who threatens to foreclose on the shoe/house if the girl does not marry him. Ollie and Stanley try to get a loan to cover the mortgage from the Toymaker who owns the factory where they work. Unfortunately, they fail to get the money when they fall into the Toymaker's disfavor. Stanley has gotten an order from Santa Claus wrong and produced one hundred operating, toy soldiers six-foot tall instead of six-hundred soldiers one-foot tall.

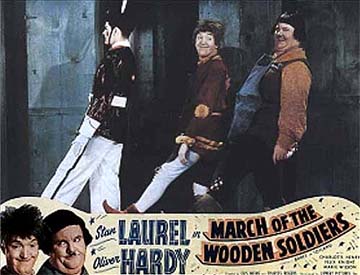

The pair finally manages to free Widow Peep from the mortgage so that Bo-Peep can marry Tom-Tom, but Barnaby gets his revenge. He gets hordes of shaggy "bogeymen" to attack Toyland. Stanley is redeemed when he and Ollie activate the oversized toy soldiers that drive the bogeymen back into the crocodile-infested swamp where they come from, saving the day. The final script plays to the comic pair's strengths with a series of wonderful routines that complement the main story. Of the twenty or so musical numbers usually featured in original operetta, four survived intact, while others were translated into instrumental form and became part of the background score. Casting the Players In addition to "Ollie Dee" and "Stanley Dum," several critical parts needed to be cast for the picture. Nineteen year-old Charlotte Henry was hired to play the innocent Bo-Peep. Despite her youth she was already a Hollywood veteran having done her first film in 1930 and starred just a year earlier in Alice in Wonderland, a role she reportedly was given over a thousand other applicants. Felix Knight got cast as the romantic male lead, Tom-Tom. Knight, at 24, was a relative newcomer to film, but had experience on the stage. He had an excellent voice and would eventually spend several years with the Metropolitan Opera Company. Knight sang many of the songs that were retained from the operetta. Probably the most difficult part to cast was that of Silas Barnaby, the wicked, old villain. During the period when he was trying to find the right actor for the part, Roach happened to attend a performance of the stage production The Drunkard. One of the play's prominent characters was a lawyer named Cribbs. Cribbs was played as a bent-over, cunning, sadistic, old man. He had just the type of disposition needed for Barnaby, so Roach, impressed by the way the part had been performed, had an interview set up with the actor.

The producer was surprised when into his office strode six-foot-five inch, twenty-one-year-old Henry Brandon. Reportedly Roach exclaimed, "You're not the old Son-of-a-Bitch that I saw the other night!" Eventually, Roach was convinced that Brandon was indeed the actor that played the part and he signed him for the film. Ironically the evil, old suitor Bo-Peep feared so much was actually played by a man three years younger than her love interest, Tom-Tom. Brandon had been born Henry Kleinbach in Berlin, Germany in 1912. He emigrated to the United States with his parents soon after his birth and had an early interest in acting. He studied at the famed Pasadena Community Playhouse before starting a career on the stage. After the Roach production, Brandon would be a well-employed actor for the rest of his life, often playing villains, but sometimes kindhearted characters as well. He continued to have a penchant for playing people unlike himself and was often cast as an American Indian or a character of middle-eastern decent despite his German heritage. Production Challenges The actual production of the film was the largest Roach had undertaken up to that time. To house the town of Toyland, two existing sound stages were combined to create a space 250 feet wide and 500 feet long. The village consisted of a number of fairy tale style buildings such as the home of the old lady who lived in a shoe, a house made out of wooden blocks, the homes of the three little pigs, a windmill, the Toyland school, toy factory and warehouse. One of the major problems was illuminating the set. In the early years of motion pictures, film was relatively insensitive to light. A huge amount of luminosity was needed to light up the set properly so that it wouldn't show up too dark on the film. The stereotypical image of a movie star wearing dark glasses didn't originally come from the need for anonymity, but because many of the early actors and actresses had their eyes damaged by exposure to the intense lights of the movie stage. After a while their eyes became very sensitive and they took to always wearing dark glasses to protect them. Typically, an area as large as the Toyland set in those early days was filmed outside in the bright California sun. Since the set was inside a sound stage, however, this meant that an unprecedented amount of lighting equipment was needed. Roach was a well-equipped studio, but it was necessary to rent arc-lights from almost every vendor in Hollywood. Many generator trucks also had to be leased to supply extra power to run the lamps. According to the studio, almost three-million watts per hour were needed to light the 812 lamps on the full set.

One special effect remembered by almost anybody who has seen the picture is the mouse. An oversized live-action rodent who resembles the animated Mickey Mouse does several scenes with an actor dressed as a cat. Many people puzzle over how this was done as the mouse is clearly too small to even be a child actor. The trick was pulled off by using a trained capuchin monkey dressed in a costume. Capuchins are among the most intelligent of monkeys and have often been used in films ever since. It seems strange today that Disney Studios would allow the use of their most prized character in another studio's film. Disney not only allowed Roach to use the mouse, he also let him utilize an instrumental version of "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf" from the 1933 animated short Three Little Pigs. Why? Maybe because in 1934 Disney was only involved in producing animation and didn't see Roach as competition. Though popular, Mickey had only been around six years at this point and not reached heights of fame he would later achieve, and his cameo in the live action film might have been thought a good way to boost his visibility. The monkey wasn't the only animal on set. In addition to mundane creatures like Bo-Peep's recalcitrant sheep, there were live crocodiles. To create the swamp scene, crocs ranging in length from six to nine feet were brought in from a Hollywood reptile farm. At the climax of the film a few of the ape-like bogeymen are forced into the water with the crocs. According to the studio, this stunt was done by expert swimmers with armed guards close by in case any of the reptiles got a little too friendly. By today's standards, the makeup and costumes for the bogeymen look laughable, but to the less sophisticated audiences of the 30's they were fairly frightening. Two hundred of the furry suits with rubber masks were made, in addition to the one hundred period costumes needed for the villagers.

While nobody was eaten by a crocodile, the production reportedly had its share of accidents and injuries. Stan Laurel tore ligaments in his right leg when he tumbled off a platform. The assistant director slid off the top of the shoe house and injured his left leg. Kewpie Morgan, who played Old King Cole, ruptured stomach muscles from the continuous laughing the part required, while Roach came down with an appendicitis. To cap it all off, one night Henry Brandon was injured in a fight at the Brass Rail bar. A Classic is Born Despite these setbacks, the production wrapped successfully after twelve weeks of filming. It was released on December 14, 1934 just in time for the Christmas season and it generally received good reviews. Variety, which had a habit of panning a lot of Laurel and Hardy efforts, praised the producer's labors saying: If Hal Roach aimed at the production of a purely juvenile picture to which children might conceivably drag their elders, he has succeeded in a measure beyond others who have sought to enter this realm. He has made a film excellent for children. It's packed with laughs and thrills and is endowed with that glamour of mysticism which marks juvenile literature. In particular, the reviewer thought that not filling the screen constantly with the comic duo's antics was a wise choice: All Mother Goose characters are woven into the plot, not to mention the Three Little Pigs, but it's Laurel and Hardy's picture. While they are on, the story zips along, but the mistake has not been made of asking them to fill the stage continuously. It is their absences which make their reappearances so effective. Finally the review ends:

This picture may not be consistently big box office, but it is the best juvenile product to date and deserves the long life it will have. In hindsight we see that the writer at Variety called this one right. The film has had a very long life. It has been a favorite with children, and children who have grown into adults. Through releases, re-releases and various name changes, including the now familiar March of the Wooden Soldiers, it remains funny and touching. It has been computer colorized twice, but it is one of the few films that doesn't seem to suffer by this modification. Its magic is likely to remain a favorite for generations to come, long after many other Christmas tradition films are forgotten Copyright Lee Krystek 2010. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|